What the Robot Saw

Keywords: AI, YouTube, social media, ranking algorithms, computer vision, machine learning, Amazon Rekognition.

On Social Media Algorithms and [In]visible Selves.

Social media ranking algorithms are driven by engagement metrics: some combination of viewer attention and interaction measurements. These algorithms dictate what videos are seen by the public. Some types of videos — “crowd pleasers” — get more visibility than others. Seasoned “YouTubers” with the knowledge and inclination to strategize their work for algorithmic appeal can maximize their visibility. And algorithms can actively perpetuate stereotypes by rewarding YouTubers for producing demographically stereotypical content (Bishop 2018) — performing selves for the camera that algorithms favor.

As a result, videos by ordinary people are often seen by few or no human eyes; as with many contemporary human actions, robots may be the main audience. What the Robot Saw is the imagined point-of-view of one such robot. The content is curated using algorithms that run counter to standard commercial ranking algorithms: only videos with low view counts and channel subscriber counts are included. The real-time cinematography derives from the fanciful directorial style of the Robot, as it pans, zooms, greyscales and edge-detects, in the process of interpreting video images. Behind the scenes, computer vision and neural networks filter undesirable clips and edit selected clips, then organize the clips into a stream-of-consciousness linear structure, focusing on subjects determined to be “talking heads.”

The film livestreams back to the internet nearly continuously as it is generated. [1] Streams are archived and linked to the Robot’s Videos page. The massive archive functions as both durational robot performance and evolving time capsule.

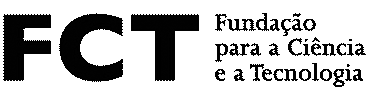

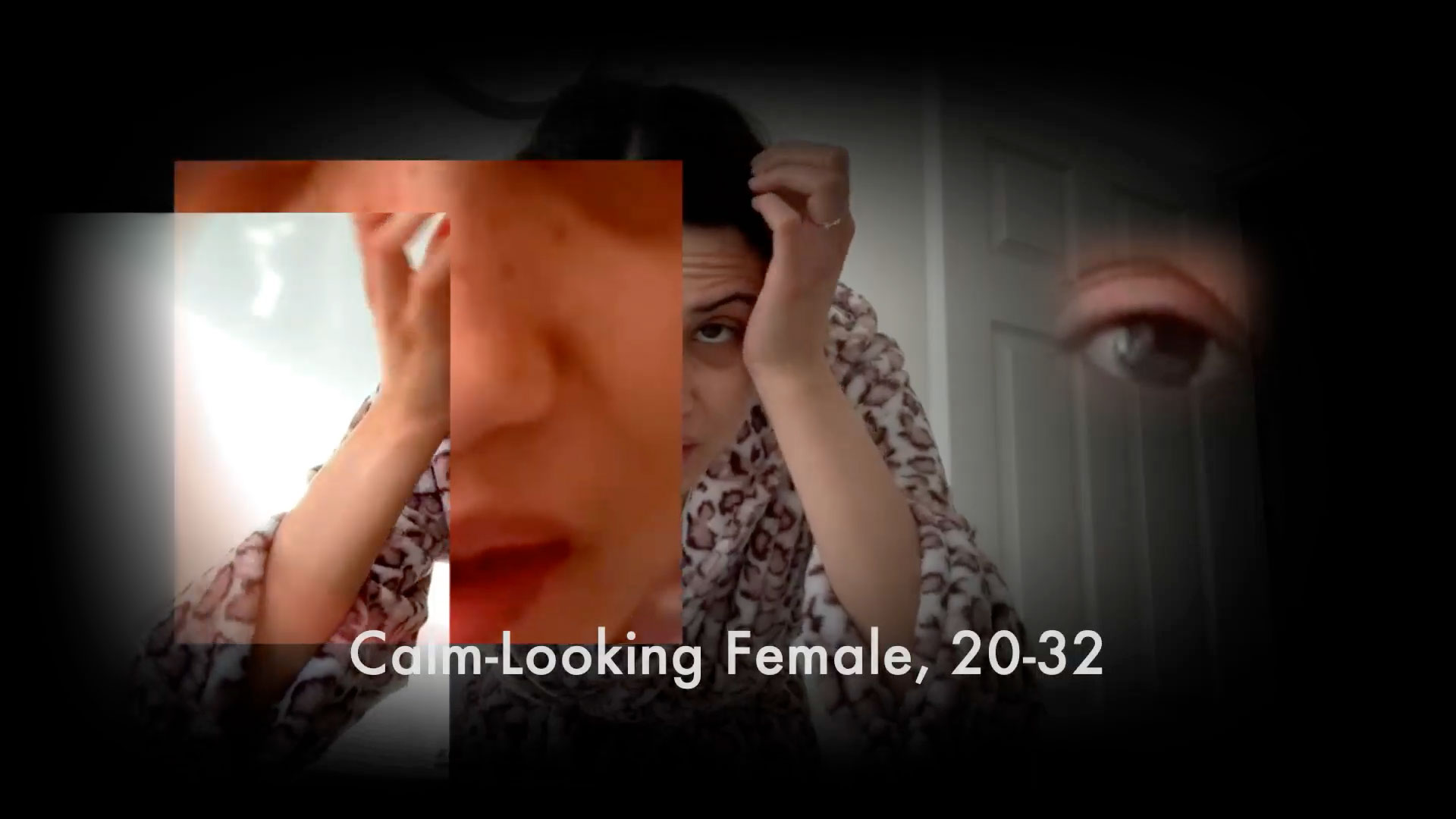

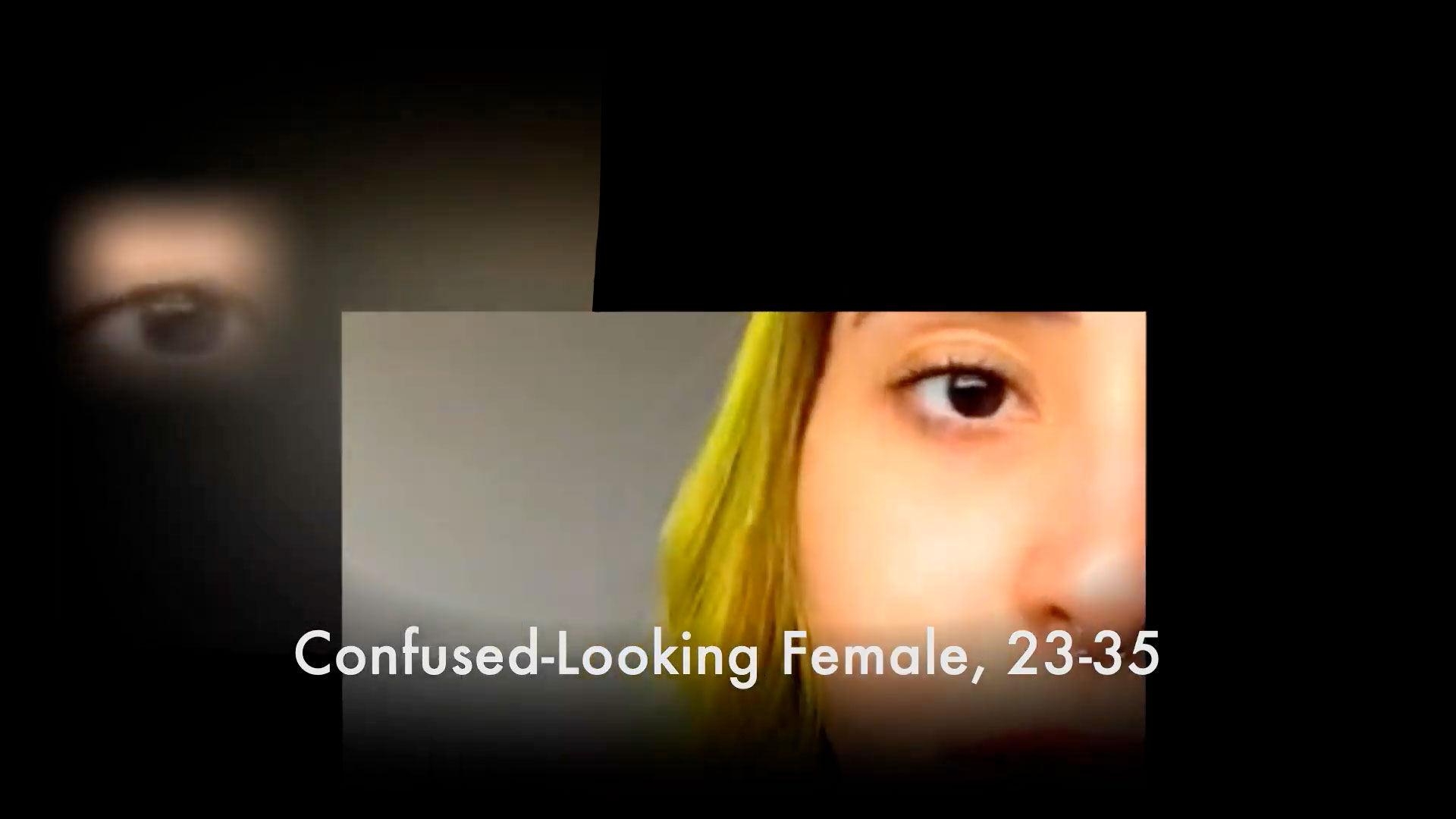

When the Robot detects talking head videos, it uses Amazon Rekognition, a popular commercial facial recognition service, to estimate age, gender, and mood as displayed in facial expression. These are the features Rekognition and similar surveillant services provide — features marketers presumably seek. These characteristics are then superimposed over the video image where viewers might expect to see an interview subject’s name and occupation. The juxtaposition of complex human faces and first-person narration with the Robot’s simplistic labels suggests the problematic nature of framing complex people according to such characteristics.

What the Robot Saw is not a pedagogy of how robots actually see.

The project’s title is a play on the expression “what the butler saw” — an allusion to early peep show films in which a voyeuristic butler spied through a keyhole [2] (Camerani 2009, 115). Both the Robot and “the butler” saw something they weren’t supposed to see. But they could only peer at the object of their obsession through a keyhole (metaphorical, in the Robot’s case.) Neither the butler nor the Robot could have a meaningful perception of the people on whom they spied.

Luciano Floridi writes that “the micro-narratives we are producing and consuming are also changing our social selves and hence how we see ourselves. They represent an immense, externalized stream of consciousness...” (Floridi 2014, 62) What the Robot Saw is on the one hand about unseen content. But it’s more broadly a response to the contemporary tangle of processes of human and robot presentation and representation -- of online and offline selves performed and perceived.

Artwork available at

Media Assets

- Video clips and archives: what-the-robot-saw.com/video-samples/

- Longer version of paper: Alexander_Paper_Full.pdf

Notes

- Periodic intermissions occur for software and hardware restarts, maintenance, etc.

- The expression actually dates back to the late nineteenth century London divorce case of Lord Colin Campbell and Gertrude Elizabeth Blood: their butler testified that he had peered through a keyhole and spied Blood with another man. In the early twentieth century the name was used for both mutoscope “peep show” machines and the moving pictures they played. Since the mid-twentieth century the expression has been used as a title for various films, plays, and television shows, usually with only a figurative connection to the original theme.

References

- Bishop, Sophie. 2018. “Anxiety, panic and self-optimization: Inequalities and the YouTube algorithm.” Convergence, 24(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517736978

- Camerani, Marco. 2009. “Joyce and Early Cinema: Peeping Bloom Through the Keyhole.” In Joyce in Progress: Proceedings of the 2008 James Joyce Graduate Conference in Rome (pp. 114-28). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Floridi, Luciano. 2014. The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality. Oxford University Press UK.

Join the conversation

xCoAx 2020: @uebergeek “What the Robot Saw”. The Robot depicts people and scenes it encounters online in an imagined cinematography style – as its computer vision and AI algorithms obsessively perceive them. https://t.co/x6O3WfXNBi #xCoAx2020 pic.twitter.com/pvenDjchsb

— xcoax.org (@xcoaxorg) July 8, 2020